This year's enrollment figures for computer science at US universities grew by just 0.2% year-on-year, after quadrupling between 2005 and 2023.

It seems the profession is about to change cycle. At Princeton University, enrollment in the degree program could fall by 25% in just two years, and at Duke, the decline in introductory courses is already around 20%, with glum predictions of the computer science bubble bursting.

Across the Atlantic, the picture is not much better: the job market for computer science graduates in the United Kingdom is at its worst since 2018, with 33% fewer job offers, due mainly to AI.

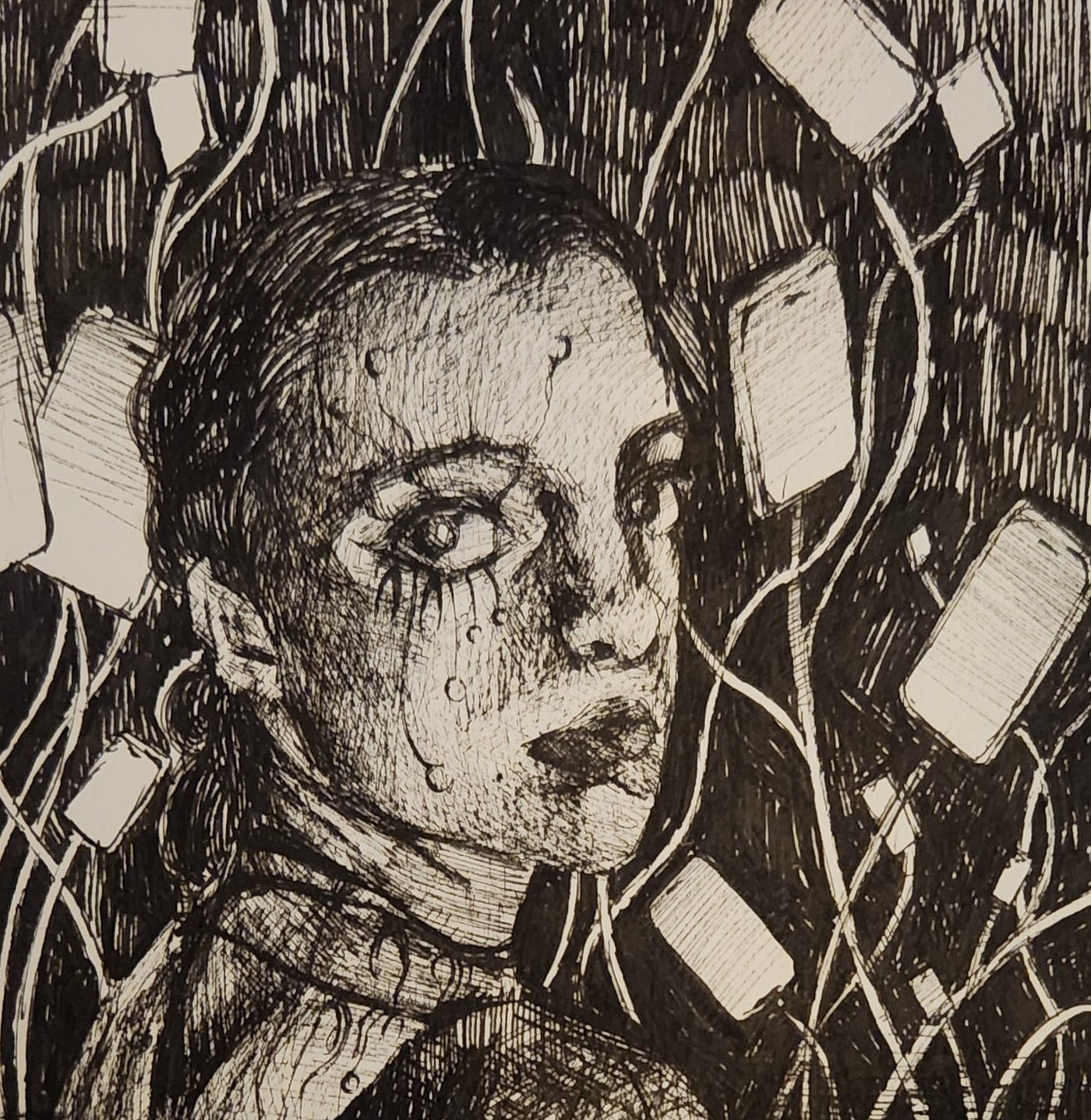

There's a bitter irony here: the very tools that developers created are changing the profession. Executives at Alphabet and Microsoft acknowledge that copilots now generate more and more code, while professionals complain that they now feel like warehouse workers, as more and more of them are being laid off. For a young person in training, learning to code is no longer a kind of lifeline, but rather means competing with machines that never sleep and never forget a semicolon.

The education sector is unsure how to respond. An article in the prestigious Communications of the ACM asks whether admission to computer science degrees should either be made more difficult, or more flexible so as to attract profiles capable of orchestrating AI systems, rather than writing every line of code. The underlying question is how to redefine what it means to study computer science, when programming is being automated.

The Evolving Landscape

The figures don't just point to cuts. Stanford's AI Index 2025, summarized by IEEE Spectrum, shows that job offers requiring AI skills have grown again, and now account for 1.8% of all job advertisements in the United States, up from 1.4% in 2023. PwC's AI Jobs Barometer 2025 concludes that workers with skills such as prompt engineering receive 56% higher salaries, while industries most exposed to AI generate three times more revenue per employee than those that still don't incorporate it. In other words, routine jobs are being destroyed, but supposedly more specialized and better-paid jobs are being created.

Everything points to a double shift: elite universities will raise the bar for training those who push the boundaries of AI development, from algorithms to distributed systems, security, ethics, etc., while there will be more applied programs to teach how to integrate generative models into business processes, design user experiences, and audit autonomous systems. There won't be fewer engineers, but different engineers: hybrid system architects, data curators, interaction designers, and above all, translators between human needs and algorithmic capabilities.

The Imperative for Professionals

For working professionals, the moral seems clear: purely mechanical skills lose value at the same rate that models are updated and their performance improves. In their place: critical thinking, communication, abstract interdisciplinary knowledge, and responsibility for social impact are gaining importance. The future of computer engineering doesn't mean the extinction of humans, but of those who do not learn, and as I have been saying for many years, unlearn at the same speed as their own tools.